Sometimes, making games is a frustrating, arduous, painful process…and then you start making the game.

Designing games is something that I find not only fun, but rewarding. Modelling stuff or doing the other “making stuff” aspects of game development, not so much. A couple of weeks ago at the Toronto Global Game Jam, I had to opportunity to make a game. In three days. With only a few hours sleep. In a smelly room. Boy was it fun…and frustrating.

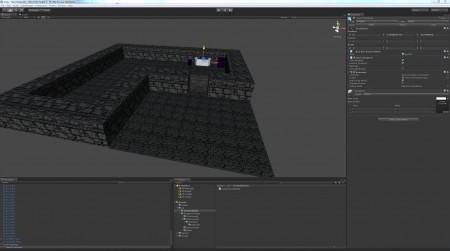

My team and I (Team Rough and Tumble Jr.) decided to make a clock-punk rogue-like dungeon crawler, with a 3D environment and a 2D character. It’s a mouthful, I know. And not something we figured was even remotely possible to do in 3 days, but we tried valiantly anyways.

The biggest issue when we started was limiting the scope. Our original design had four characters (soldier, witch, monk, and mechanic); five environments (Forest, Mountains, Mountain Temple, Cathedral Basement, and the Town); different combat mechanics for each character (the soldier used cooldowns, the witch used health as a resource, the monk used body temperature to enhance his attack and defense, and the mechanic used a robot); and let’s not forget the Rogue-like dungeon creation. It’s a lot for even a seasoned development studio to do, let alone a bunch of fledgling designers with three days. We decided early on to limit the scope as much as possible, and then add more with any time remaining. We ended up with one character instead of four, one level instead of five, one enemy that was a recolour of the character, basic AI; these were the kinds of limitations we put on ourselves in order to have any chance of success. Limiting scope this much also helps protect against feature creep, which is when additional, unplanned features get added as development goes on (because hey, adding a flaming particle effect to the sword is really cool, right?). The less you’re aiming for, the less impact little extras have on your development time.

The other issue we had was employing friends who had never done a game jam before. There was two of them, and they’re 2D artists; but they had never done a game jam before and the environment we were in ended up more as a nerf-war and less of a game development studio. Don’t get me wrong, having introduced nerf to the rest of the team after the jam has proved very stress-relieving (even for the professors); but during the jam, it did more harm then good. Distractions during game jams, and indeed during all of development, are something that you need to keep in check at all times. We ended up with the roughest of rough alphas because of the distractions.

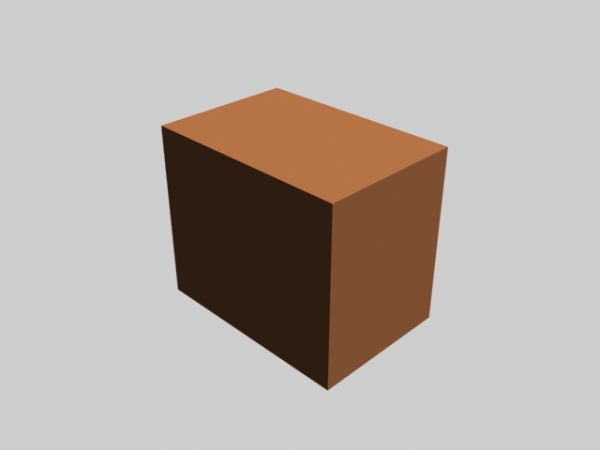

In the end though, we have a proper alpha, and below you’ll see a screenshot of one of the interior buildings in the Town being built (it’s all very rough, mind you). We managed to get the town exterior done, the dungeon is indeed randomly generated (with proper spacing too!), and while we have a fair ways to go with it, it’s coming together.

Protip for doing any game jam: design small, implement quickly, and do the cool stuff at the end if you have time. I’ve done three jams so far (Game Prototype Challenge and TGGJ 2012/2013), and this was the first and only time I’ll attempt something this big.

BrutalGamer Bringing you Brutally Honest feedback from today's entertainment industry.

BrutalGamer Bringing you Brutally Honest feedback from today's entertainment industry.